| The Book Thief: A Score Analysis |

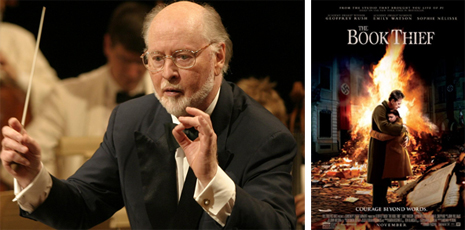

| John Williams accompanies Death on an exquisite visit to Himmel Street. |

| By David Kay |

|

John Williams fans were in for an unexpected treat late last year—in early August it was revealed that the composer would be scoring his first non-Spielberg film in eight years: The Book Thief. Presumably, Williams agreed to score the picture due to his love for the critically acclaimed book of the same title. The resulting score is a beautiful, delicate work, even if it draws heavily on previous pieces by the composer. Thematically, the score focuses on the ability of art to transcend death. [Warning: Spoilers follow!] The film, set in Nazi Germany, tells the story of Liesel, a young Russian girl adopted into the Hubermann family, who live on Himmel (Heaven) Street. Narrated by Death, the film charts the sacrifices civilians are forced to make in a period of total war. For the Hubermanns this task is complicated when they agree to hide an escaped Jew named Max from the Nazis. The film gets its title from Liesel—initially illiterate—who learns to read and write in a society that burns off-message books. She starts stealing books from the library of a wealthy Nazi. At the end of the film, Allied forces accidentally bomb Himmel Street, killing almost everybody Liesel has come to love. Max survives, having left midway through the film; the film ends with Death narrating that Liesel became a writer, and both she and Max lived into their old age. Williams’ score gets an incredible amount of mileage from the use of the minor scale, as virtually every theme and motif incorporates it. First and foremost is the idea that opens the album and the film: a motif for untimely death (not to be confused with the character in the film, Death). The idea is basically just the ascending first five notes of a minor scale, absent the fourth scale degree. The use of such a common musical line creates a sense of inevitability, as the ear almost knows where the motif is headed, just as Death knows “one small fact: you are going to die.” But because Williams skips the fourth scale degree and switches from eighth notes to 16th notes after the first pitch, we also feel that the arrival at that inevitable destination is a bit rushed; hence it is a motif for untimely death. The figure pops up throughout the score; when Liesel first enters the Hubermann household we hear it played backwards. The same retrograde variation occurs again when she steals a book from the remains of a Nazi-sanctioned book burning. It shows up yet again when Liesel is granted access to the library of a powerful Nazi. This reversal suggests that the scenes it accompanies challenge untimely death—in the first instance, the power of the family can prevent untimely death (as in both Max’s and Liesel’s case), and in the second two, the power of books can transcend death by giving voice to an author who is biologically expired. Finally, the first three notes of this motif are heard—again, played backwards—in the “Finale,” as Death reminisces over Liesel’s life as a successful author. Because only the first three notes of the motif are used in this instance, the absent fourth scale degree no longer gives us a sense of a truncated journey (if one starts on the third scale degree and goes down, the fourth is not an expected part of that journey); in this way Williams acknowledges that Liesel’s death was not untimely, while maintaining the ability of books to counteract the end of one’s physical existence (as the motif is still played backwards). This is the ultimate indication of books’ powers to overcome death—if Liesel’s ideas can live on after she has passed, is she really dead? From this ascending motif, Williams derives a more direct idea for reading and writing, one that describes the “magnetism” Liesel feels pulling her towards the books. This idea is essentially a fluidly ascending and descending minor scale—an indication of reading and writing’s effortless ability to transcend the physical conception of life and death. The character Death also receives a more identifiable theme (or as Williams calls it, the theme for “Providence”), often played in conjuction with the untimely death motif, which becomes an accompaniment. Death’s melody is slightly reminiscent of a theme from Williams’ Seven Years in Tibet, but it seems to be more directly influenced by the “Tuba Mirum” from Mozart’s Requiem Mass. This is a fitting reference, as requiem masses are obviously closely associated with Death. As discussed earlier, in the motif for untimely death, the fifth scale degree represents the final destination on the journey of life: death. Death’s theme starts on this fifth scale degree—for instance, when the two are played together in the opening of “One Small Fact,” the untimely death motif ends on a concert G, the same note that Death’s theme begins on. Death is the agent that brings about the result of an untimely passing. To make the derivation perfectly clear, the theme then descends down a minor scale.

Certain elements of Death’s theme are hidden in key moments of the score. For instance, the most emotionally intense cue in the score, “Rudy Is Taken,” is heard as Liesel reacts to the death of her family and friends. The sequence is filled with sudden key modulations, indicating Liesel’s emotional instability as wave after wave of realization hit her and she painfully starts to understand that virtually everybody she cares for is dead. The sequence is almost entirely based on an ascending line from Death’s theme; for the most straightforward variation, compare the ascending line at 1:21 of “Rudy Is Taken” to the one at 0:49 of “The Book Thief.” At the end of the film, Death describes Liesel’s life, and how she lived until she was 90 years old. At this time Williams provides a gorgeous transformation of Death’s theme; the melody is almost unchanged from its minor-mode origin, but now begins on a different scale degree and is set in major, altered to produce a warm (if bittersweet) feeling. Instead of sounding cold and stubborn, the theme is now affectionate and friendly, representing the sense of serene acceptance that Liesel has over her passing; the contrast between this and “Rudy Is Taken” is extreme. While perhaps slightly derivative of the piano line in the second movement of Dimitri Shostakovich’s second piano concerto, the “Finale” is a beautiful way to end the film. Liesel herself also receives a theme, which bears some superficial resemblance to one from Williams’ Angela’s Ashes. First receiving a grandiose statement in the opening track, which serves as a sort of mini-overture for the film, the idea is then scaled back and given space to develop with Liesel. Williams chooses to use the theme mostly when she experiences events that impact her life significantly; for instance, it is hinted at on the French horn as she travels to her new home. As she walks to the house of the Nazi Burgermeister, whose wife will grant her access to a large library, we hear her theme again, indicating that reading will become a significant part of her identity; when Max gives her a painted-over copy of Mein Kampf that says “write” in Hebrew, her theme sounds once more, only this time with several new phrases added on, indicating how writing furthers her development. The construction of this theme is noteworthy: The first five notes ascend to a wistful, yearning long-note, indicating a sense of cautious hope. However, this is short-lived, as the line soon descends down the first four notes of a minor scale; death has played an important role in shaping Liesel. These four descending notes show up in other points of the score: They are featured extensively when Hans leaves, having been drafted to fight with the Nazis. They also appear when the Burgermeister catches his wife allowing Liesel to read in their library and bans her from doing so, once again associating death with the suppression of literature. The theme for Max, which recalls a melody from Williams’ Stepmom, is probably the most accessible in the score, although it receives very little screen time in the film. By starting with a repeated note that contrasts with the descending harmony (a harmony that, for the first four chords descends down the minor scale, starting at the tonic), Williams hints at both Max’s persistence to survive the array of obstacles in his path (the steady note) and his proximity to death (the descending harmony). This fear of Max’s untimely death is also more directly indicated; the untimely death motif is directly woven into the melody. Max’s theme does not receive much variation throughout the score, but its simple beauty provides a ray of light in a dark story.

To represent Liesel and Max’s budding relationship—and the literary fruits it brings the former—Williams writes a motif that again brings to mind one from Angela’s Ashes, to the point that it’s likely that “Plenty of Fish and Chips in Heaven” was used in the temp track at some point. In any case, the adapted version in The Book Thief is also derived from Max’s theme; the fifth, sixth, seventh and eight notes of the latter follow the same intervallic patterns as the third, fourth and fifth notes of the former. The relationship motif shows up in key moments involving their bond, including when Liesel reads H.G. Wells’ Invisible Man to Max as he attempts to recover (readings that he later says “kept me alive”), and when Liesel admits to Rudy that she is illegally hiding a Jew. The motif is briefly referenced in the cue “The Visitor at Himmel Street.” Readers who have not yet seen the film might be surprised to learn that this serene piece accompanies a scene where a bomb lands on Himmel Street, killing almost everybody that Liesel knows. The juxtaposition between the music and the visuals—not to mention the contrast in mood between “The Visitor at Himmel Street” and the following cue, “Rudy Is Taken”—suggests that the most tragic and difficult part of death is the effect it has on the living. The Max/Liesel relationship motif represents how their relationship and Liesel’s interest in literature literally saves her life; the only reason she is not killed in the blast is because she falls asleep in the basement while writing her story in the whited-out copy of Mein Kamp that Max gave her. So why did John Williams, who has recently chosen more projects based on the people involved (for instance, we can look to his continued collaborations with Steven Spielberg, Gloria Cheng and “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band as proof of this), decide to lend his voice to this story, of all the available options? I believe the answer lies in the attraction the 82-year old composer felt towards the thematic statements the film makes. Williams is a composer whose artistic output has impacted our society in a very profound way. Whether one credits him for sparking the Symphonic Renaissance of the ’70s and ’80s, getting people interested in all kinds of orchestral music in an era when such interest was desperately needed, or adding his own original voice to the worlds of music and of film, it is clear that his artistic decisions will continue to be felt for generations to come. Perhaps with The Book Thief Williams meant to deliver one small fact: that no matter what happens to him, he will be around for a long, long time. —FSMO

|