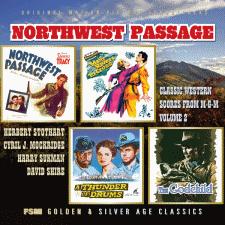

The Godchild

Peter B. Kyne’s short story “The Three Godfathers,” published in the November 23, 1912, edition of the Saturday Evening Post, proved popular enough for him to expand it into a novel published the following year, and before the long the tale served as the basis for several films, beginning with a 1916 silent picture starring Harry Carey. Carey also starred in a 1919 remake, Marked Men, directed by John Ford, while William Wyler helmed the first sound version, Hell’s Heroes, in 1929. These three incarnations came from Universal Pictures, but M-G-M then filmed the property twice, first in 1936 as Three Godfathers, and most memorably in 1948 as 3 Godfathers, starring John Wayne and with John Ford back in the director’s chair. When Wyler visited Ford on his deathbed in 1973, Ford reportedly joked, “It’s time for you to do Three Godfathers again.” That distinction would, however, go to a young director named John Badham.

Badham got his start directing episodes of series such as The Bold Ones; his first TV movie, The Impatient Heart, debuted in October 1971. David Shire provided the score for that film, and around the same time the composer and director both worked on the pilot for Sarge, a short-lived series starring George Kennedy as a cop-turned-priest, with a standout theme from Shire. Badham and Shire would collaborate again on the 1973 telefilm Isn’t It Shocking?, starring Alan Alda as a small-town sheriff investigating gruesome murders.

Badham would direct four made-for-television movies first broadcast in 1974: The Law, The Gun and Reflections of Murder (a remake of Les diaboliques set in the Pacific Northwest), as well as The Godchild. Yet another retelling of The Three Godfathers, The Godchild (which debuted on November 26, 1974) follows the same basic storyline as its predecessors, in which three fugitives find nobility by taking responsibility for an orphaned infant while on the run from the law. Ron Bishop’s script does add one twist to the familiar premise, setting the action during the Civil War and making the three fugitives escaped Union POWs on the run from Confederate soldiers in 1860s Texas. Jack Palance, Ed Lauter and Jose Peréz star as the fugitives, with Keith Carradine and Jack Warden among the pursuers. Badham shot the film on location near Tucson in Arizona, and in Red Rock Canyon and the Mojave Desert in California, telling one interviewer in 1974: “It’s not the type of film that can be shot on a backlot because geographic setting is paramount to the believability of the story. It’s three men and a baby pitted against Mother Nature’s barren, blistering desert.”

The mid-1970s were an especially productive period for composer David Shire as well. The year 1974 alone saw the debut of no fewer than eight TV movies featuring his music, everything from Killer Bees to Lucas Tanner. Not to mention two feature scores often ranked among the most innovative of the period, The Conversation (scored for solo piano and performed by Shire himself) and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (featuring a remarkable 12-tone score, available on CD from FSM as Retrograde FSM-80123-2). Given the hectic pace at which he must have been working, it is unsurprising that the composer, when asked recently about his score for The Godchild, had no recollection of the project whatsoever.

Shire captures the Texas locale and Civil War era with a sparse score for 15-piece ensemble that prominently features guitar. The composer plays up the sarcastic camaraderie of the fugitives with a wry, bluesy theme, but also conveys their impending doom with a recurring ostinato that suggests the Dies Irae. While the score does not represent the film’s (mostly unseen) threat—Apache Indians—the Confederate soldiers receive austere music for winds and timpani during the main title, material that returns later in the film. The final cues focus on a wholesome melody for the relationship between the godchild and his caretakers, the theme typically voiced on solo woodwinds such as bassoon under delicate harp accompaniment.

- 26. To the Sentries

- The opening titles unfold over nighttime footage of Fort Jebbins, a Confederate stockade, where Union soldiers Rourke (Jack Palance) and Crees (Ed Lauter) are incarcerated. Shire introduces a plaintive theme for woodwinds that rises and falls over a foreboding timpani echo during establishing shots of soldiers standing watch. Bluesy woodwinds and guitar underscore Sgt. Dobbs (Jack Warden) riding out the front gate to check on two lazy sentries, Crawley (Bill McKinney) and Loftus (Jesse Vint).

- 27. Taking a Look

- Guitar and bass sound as Crawley and Loftus investigate a strange noise. After they come upon a pair of horses, the cue drops out momentarily as Sánchez (José Pérez)—an accomplice of Rourke and Crees—incapacitates the sentries. Shire develops the main title material on timpani, violins and bass clarinet for Sánchez checking his watch: in a subsequent unscored sequence, he springs his cohorts from their cell with a dynamite explosion at the stroke of midnight.

- 28. Into Town

- A Stravinskian violin figure alternates with horn and woodwind phrases as the fugitives arrive in a Texas town. Guitar and timpani recall the foreboding figure from the main title as Rourke and Crees enter a bank, with Sánchez standing vigil outside. Inside the bank, woodwinds and violins underscore Rourke’s friendly interaction with a customer’s baby.

- 29. “In Here, Nat”

- Rourke and Crees order banker Nathaniel Mony (Kermit Murdock)—pronounced “money,” to the amusement of the thieves—to fill their sack with cash; a wry piece for guitar, clarinet, bassoon and violins underscores the holdup.

- Texas Gringos

- Shire develops the fugitive ostinato from “Into Town” as Rourke and Crees rejoin Sánchez outside the bank. After they ride off, the cue bleeds through a transition to Mony informing Confederate Lt. Lewis (Keith Carradine) of the robbery.

- 30. Movin’ Out

- While camped out in the desert, the fugitives spy on a Confederate train as it slows in the distance. Clarinet and horn sound over a motor of strings, guitar, piano and percussion as Rourke instructs his cohorts to remove the shoes from their horses: the tracks they create will give the impression that Comanche Indians are in the vicinity. Shire’s cue continues as soldiers search the desert for the outlaws, with Dobbs and Crawley discovering their fresh horse tracks.

- 31. Umbrellas

- In addition to the misleading tracks, the fugitives start a series of Comanche-style fires in the desert. After Dobbs and Crawley fall for the scheme, a woodwind passage underscores the outlaws extinguishing the fires. A bluesy “traveling” melody then unfolds over the fugitive ostinato as they ride through the desert; Rourke reveals that he plans to sell umbrellas with his cut of the stolen money.

- 32. Water Hole

- Still on the hunt for the fugitives, the Confederates arrive at a watering hole, with contemplative guitar sounding as their horses drink. The traveling tune from “Umbrellas” returns on strings, decorated with twangy guitar over a plodding bass line for a transition to the exhausted, dehydrated outlaws walking through the desert with their remaining horse.

- Dead Horse

- Rourke puts the horse down after it collapses from a lack of water. Shire’s unused cue for this scene features a grating chordal pyramid—representative of the horse’s pain—that rises against a noble, stepwise melody for the outlaw’s act of mercy.

- 33. Desert Trek

- Shire reprises the belabored development of the traveling theme as the weary outlaws proceed through the desert, surviving on horse blood.

- The Schooner

- The outlaws excitedly arrive at a water tank only to find it has been dynamited. Impressionistic interplay for woodwinds and strings underscore the men searching the surrounding area, with aching violin sounding over clarinets when they discover a broken-down covered wagon nearby. The cue reaches a solemn, chordal finish as the outlaws find Virginia (Fionnula Flanagan), an ailing pregnant woman in the throes of labor. Her husband, William (Neil Brooks Cunningham), has wandered off to search for water. In his absence, the outlaws help deliver Virginia’s baby during a terrible sandstorm; before she dies, they swear to act as godfathers to her child.

- 34. William Returns

- An unused cue features the traveling theme on horn for the outlaws setting off on foot with the baby. The film cuts back to the wagon, where Shire intended yearning violin against flute accompaniment to underscore William returning and weeping for his dead wife.

- 35. Papa Cress

- In another unused cue, bass clarinet introduces a wholesome theme for Virginia’s baby, followed by reprises of the violin melody from “William Returns,” and the traveling theme. (It is possible Shire wrote this cue to accompany deleted footage.)

- 36. William Returns

- Shire reprises the baby’s theme on bassoon over gentle harp accompaniment as Crees feeds the infant milk. The cue dies away before a crazed William arrives on the scene and confronts the outlaws for supposedly killing his wife. He shoots Sánchez and Crees—who gives his life to shield the baby—before Rourke guns him down in return.

- A Baby?

- After the outburst of gunfire, Rourke calms the startled baby, with bassoon and English horn developing the infant’s theme; this material alternates with chordal woodwinds as a puzzled Crawley and Loftus arrive and question Rourke.

- 37. “This Is All That There Is”

- Dobbs, Crawley, Loftus and Lewis have lost their water mule in a sandstorm, and as Rourke knows the dangerous, Apache-filled territory better than anyone, the soldiers agree to allow him to lead them back to civilization. Although the baby will slow their progress, Rourke resolves to take the child along, to a solo bass flute reading of its theme. Shire scores a montage of the men traveling through desert with the violin line from “Into Town” over rippling accompaniment. Introspective woodwinds close the cue as the men settle down in rocky terrain.

- 38. Let’s Get Going

- The Confederate material from the main title returns for Dobbs patrolling the area around the party’s camp at night; grating electronics sound when he an arrow strikes Dobbs in the back and Apaches attack. A subsequent clarinet reading of the baby’s theme is dialed out of the film as Rourke nurses the child back at the campsite. The cue returns to the film when Lewis reluctantly agrees to feed the baby, allowing Rourke to check out the surrounding area. A descending line from the main title sounds over a deep pedal when morning arrives, with Rourke returning to inform Lewis that the other soldiers are dead, murdered by Apaches.

- 39. Adios

- Rourke volunteers to distract the Apaches by sacrificing himself so that Lewis can escape with the baby. Before he heads off, he tells the lieutenant that it would have been an honor to serve under him given different circumstances, and asks that he someday tell the child, “how proud his godfathers was of him.” Bass flute and guitar state the baby’s theme as Lewis considers Rourke’s final words. The film segues to the lieutenant at a Confederate hospital with a dreamy, stylized transition underscored with austere violins—suggestive of a rising line from the main title—over flowing textures.

- End Title

- After Lewis is reunited with the baby at the hospital, bassoon and guitar play the infant’s theme under a delicate harp ostinato when he names the child after himself and the three fallen godfathers. The melody continues through the end titles as the lieutenant delights in holding his new son. —