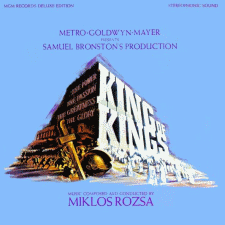

King of Kings

Disc 12 of this box set presents the 1961 King of Kings soundtrack album re-recorded in Rome—never before presented on CD in true stereo—as well as previously unreleased alternates and outtakes from the original King of Kings recording sessions in Culver City.

MGM Records Soundtrack Album

MGM Records was a major American label during the 1950s, with such artists as Connie Francis and Hank Williams Jr. heading its catalog. Its primary focus, however, was always movie soundtracks, beginning with Till the Clouds Roll By in 1946 and ending with a series of musical anthologies in 1974. In 1960, the label initiated a series of specially packaged soundtrack albums with Ben-Hur, followed by King of Kings, The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, Mutiny on the Bounty, How the West Was Won, Doctor Zhivago and others. The initial four releases in this series were issued in deluxe box sets containing the LP and a hard-cover souvenir program—packaging that was soon abandoned in favor of gatefold covers (sometimes with a booklet glued inside) and, eventually, standard LP jackets.

It was most appropriate that the first two releases in this series should be devoted to M-G-M’s “star” composer, Miklós Rózsa. Neither used the actual film recordings, however; in both cases, label executives decided to re-record the music in Europe for financial reasons. This meant that the actual film soundtracks would go unheard (apart from the films themselves) for decades, until Sony released about 75 minutes of the original King of Kings music tracks in 1992 (AK 52424) and Rhino Records released a 2CD set of the original tracks for Ben-Hur in 1996 (R2 72197), followed by a complete 2CD King of Kings in 2002 (R2 78348). Nonetheless, this situation had the positive result of giving the composer an opportunity to rethink his scores in “concert” terms: cutting, reshaping, re-orchestrating and, in a few instances, even rewriting his cues for performance apart from the films. Thus, these LP albums stand as unique musical compositions in their own right, and provide fascinating insight into the composer’s creative process.

Initially, the King of Kings film soundtrack was to be recorded in London where, at the same time, a separate LP album would be taped as well. By January 1961, the plan had been changed due to the unavailability of the London studio, and the soundtrack was scheduled to be recorded at M-G-M Studios in Culver City instead (the sessions ultimately took place there between February and May of 1961). That left open the question of where in Europe to record the album. (At the time, the U.S. musicians’ union “re-use” fees made it too expensive to release the film performance on a record album.) Rózsa favored making the disc in Rome with EMI engineers (as he had with Ben-Hur), but London was also considered, along with two German cities (Nuremburg and Hamburg—in which case the recording would have been engineered by Deutsche Grammophon). Rome was the final choice, primarily because it was the cheapest alternative (costing approximately half of what it would have cost to record in London). On June 6 and 7, 1961, the composer conducted the Symphony Orchestra of Rome and the Singers of the Roman Basilicas in a 40-minute sequence that he had assembled specifically for the album. The disc (1E2/S1E2—a box set with souvenir book and 4 film stills) was released in November 1961, along with two spoken-word albums using Rozsa’s score as background. The following January, producer Samuel Bronston proudly distributed 120 copies (along with the El Cid album) to Academy members in hope of securing an Academy Award nomination for either score; he succeeded with El Cid, which ultimately lost to Henry Mancini’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Subsequently, there were two major reissues of the King of Kings LP: by British Polydor in the 1970s, and by American MCA in 1986. The album debuted on CD from British EMI Records (CDP 79 4987 2) in 1990 (coupled with the soundtrack album to The Greatest Story Ever Told). Unfortunately, all 1980s and ’90s editions of the album (on LP and CD) have been in cramped mono or “electronic” (fake) stereo as the true stereo album masters had gone missing—and remain lost to this day. The true-stereo master had, however, been released on commercial open-reel ¼″ tape by MGM Records at the time of the film’s release, and thanks to the generosity of Rózsa Society members Mark Koldys and Herb Norenberg is presented on disc 12 newly mastered from their personal copies of that now-scarce open-reel release.

There is some confusion about the intended order of tracks 13 and 14 on this disc. Almost all versions of the album (including the original boxed set, its reel-to-reel equivalent and both the British Polydor and American MCA reissues) feature “The Scourging of Christ” preceding “The Way of the Cross,” as on this disc, following the logical film order. This is also the order laid out in the original liner notes written by Rózsa himself. Yet a Japanese reissue and a German pressing of the original MGM Records LP sequenced “The Way of the Cross” first and that is how the two tracks are listed on the labels of virtually all editions.

A memo from album producer Jesse Kaye, written after the recording sessions and found in the MGM Records file, instructs that the liner copy should be changed as follows:

• The title of side one, band 2 (which was originally “Pompey Enters the Temple”) should be changed to “The Holy of Holies.”

• The title of side two, band 3 (originally “Christ’s Entry Into Jerusalem”) should be changed to “Christ’s Entry Into Jerusalem and Tempest In Judea.”

• On side two, bands 4 (originally “The Scourging of Christ”) and 5 (“The Way of the Cross”) should be reversed, placing “Way” before “Scourging.”

For the original MGM Records boxed set, these changes were indeed made on the disc label but not in the composer’s liner notes or on the discs themselves. FSM has used the revised cue titles but chosen to program “The Scourging of Christ” before “The Way of the Cross” because that sequence will be most familiar to veteran collectors and it follows the story in logical fashion. There also seems to be no compelling musical reason for switching them, in spite of Kaye’s memo.

George Komar has provided a thorough description of the score in his commentary for the Rhino soundtrack issue, so the following notes will focus primarily on the differences between film and album versions, with references to the film cues Rózsa used when adapting his score for “home listening.” In addition, the composer’s own liner notes have been reproduced below. Rózsa made many changes when refashioning his music to be heard away from the film—mostly minor ones but a few major ones as well. One will never know if he thought of these as practical condensations of a greater whole (a sort of “Reader’s Digest” version of the film cues) or innate improvements to the score, made when he was free to follow his own musical instincts away from the “tyranny of the stopwatch.” In either case, he has left behind two closely related but subtly different compositions—both of which one is happily now free to enjoy.

- 1. King of Kings Theme—Prelude

- This ecstatic rendition of the principal theme is exactly as heard in the film, except for a “concert” ending in place of the segue to “Roman Legions.” The Singers of the Roman Basilicas are slightly more forward in the mix than their Hollywood counterparts.

- 2. The Holy of Holies

- An album arrangement of the music for the opening temple scene, this track begins with “The Scrolls” (Rhino, disc 1, track 5), but at 0:37 Rózsa leaves the film version behind. Here, on the album, he repeats the theme with an added woodwind counterpoint that is not on the soundtrack at all, and adds a short new coda.

- 3. Pontius Pilate’s Arrival Into Jerusalem

- Rózsa adopted a slightly faster tempo for this performance, and added a rousing “concert” ending (beginning at 1:48) not used in the film. The composer used this same adaptation, including the two-measure introduction, in the piano folio published by Robbins Music at the time of the film’s release.

- 4. The Virgin Mary

- For this album version, Rózsa restored a one-measure cut made in the second section on the soundtrack (at 0:59 of Rhino disc 1, track 8)—a cut probably made to match the film’s timing rather than for musical reasons. He also revised the orchestration, assigning the melody of the second section (beginning at 0:27) to solo flute rather than violins (as heard on the soundtrack). The ending is slightly extended here to provide a more satisfactory conclusion.

- 5. Nativity

- Again, a slight extension of the concluding phrase distinguishes this album version from the soundtrack. It also corrects a very slight (but surprising) error made by the M-G-M Symphony near the end (at 3:27 of Rhino disc 1, track 6) where the basses get ahead by one beat, thankfully for just half a measure! (It is also possible that an M-G-M copyist made a mistake that the composer did not catch and correct at the recording session.)

- 6. The Temptation of Christ

- Rózsa completely reworked this cue for album presentation. A slightly swifter tempo and several extensive cuts (even beyond those already made for the film, as indicated in Komar’s notes) have foreshortened the cue considerably. Here Rózsa focused entirely on his “satanic” twelve-tone motive until the Christ theme (with added chorus) triumphs in the extended jubilant conclusion.

- 7. John the Baptist

- This album presentation of the Baptist’s theme is based on “John’s Message” (Rhino disc 1, track 23). Slight changes in rhythm, orchestration and development (especially in the second half) presumably represent the composer’s final thoughts, since he preserved the same rhythmic and melodic changes in the piano folio version.

- 8. The Miracles of Christ

- This track was carried over from the cue “Miracles” (Rhino disc 1, track 16) with no apparent changes.

- 9. Salome’s Dance

- Komar details how severely truncated the six parts of this dance sequence were in the film. Here, in the album version, it can be heard complete, with each part flowing effortlessly into the next, building inexorably to its frenzied conclusion.

- 10. Mount Galilee and the Sermon on the Mount

- For the “solemn liturgical processional” that opens this track, Rózsa reverted to the version first heard in the “Overture,” with its striding bass line and choral voices, rather than the more austere orchestration heard in the film. After the initial theme appears a second time (transposed up a fifth), the composer jumped from the “Overture” to the equivalent of 2:28 on Rhino disc 1, track 28, thus leading to the Beatitudes theme. Unlike in the film, that theme is heard here with chorus, although only on a neutral syllable (“ah”) rather than the actual text from Matthew.

- 11. The Prayer of Our Lord

- This album track is a “concert” version with little in common (other than the obvious thematic material) with the corresponding Rhino track (disc 2, track 1). Komar points out how the music is truncated in the film to fit the scene; this version is complete, the orchestration is fuller, the harmony is richer and the chorus sings the actual biblical text rather than just “ah.” It is a close (but not exact) match for the published choral version, once available from Robbins Music but now long out of print.

- Two alternate presentations of this track can also be found in this box set. Disc 12, track 34 (closing the King of Kings disc) features the original Italian-performed version recorded in June, warts and all, as found on an early pressing of the LP, and kindly provided for release by William Ankenbrock and John Fitzpatrick from Ankenbrock’s rare copy. Disc 13, track 27 (which would not fit on disc 12 due to space limitations) is the underlying instrumental track that was used to make both choral versions—as found on a ¼″ stereo tape in the Warner Bros. archives.

- 12. Christ’s Entry Into Jerusalem and Tempest in Judea

- For the first minute and a half, this LP track follows “Jesus Enters Jerusalem” (Rhino disc 2, track 6), although there is a slight change in orchestration (celli on soundtrack, low brass on album) at 1:09. Then the LP version jumps over a bit of bridging material to land in the midst of “Tempest in Judea,” which is played at a somewhat slower tempo on the Rome recording. Since the album version skips over the next film cue, “Defeat,” Rózsa repeated the last phrase of “Tempest” a step lower in order to be in the proper key for the following cue, “Phalanx.” The first, percussion-only bars are understandably cut on the LP, since they primarily represent a visual moment in the film. The composer adopted a much swifter tempo for the Rome version, cut a few bars for conciseness and added one more blast from low brass at the end for a more conclusive cadence.

- 13. The Scourging of Christ

- This track combines the soundtrack cues “The Scourging of Christ” and “Crown of Thorns” (Rhino disc 2, track 11) with just minor alterations. The break caused by a reel change (0:13 on the Rhino) is eliminated, a few measures of repeated material are dropped here and there, and the piece ends with the “sinister four-note figure” mentioned by Komar, rather than concluding with Judas’ motive.

- 14. The Way of the Cross

- A more concise treatment of the “Via Dolorosa” theme than the film version, this album track matches the soundtrack (beginning at 0:37 of Rhino disc 2, track 12) only through the passage where Jesus falls underneath the cross. At that point, Rózsa cut a few measures to shorten the middle section of this ABA-form piece, and made even more cuts for the album track when the music returns to the opening theme. A comparatively long section from the film soundtrack, where the tonal center shifts briefly from its rock-solid “A” to “E” (3:13–3:45 on the Rhino), is missing from the Rome version. One wonders if the composer felt that the album version was the “ideal” musical representation of the theme, with the cut portions being essential to the film’s timing but dispensable from the musical argument. That suspicion is strengthened by looking at the piano folio version, which follows the LP exactly (except for even further small cuts in the midsection of the piece!).

- 15. Mary at the Sepulcher

- This LP track actually restores three single-measure cuts that had been made on the soundtrack (hear them at 0:42, 1:09 and 1:51 on this disc). Curiously, the bass line in one measure on the soundtrack (at 2:23 on Rhino disc 2, track 12) is a third lower than it sounds here (and as it is written in the piano folio version). Perhaps this is a copying mistake (or Rózsa may have changed his mind between Hollywood and Rome).

- 16. Resurrection—Finale

- This album track parallels closely, but not exactly, the final musical moments of the film. It begins with “Resurrection” (3:28 on Rhino disc 2, track 13) and remains unchanged until near the end, where the transition into the “Epilogue” (the “Lord’s Prayer” theme) is slightly transformed. Instead of bringing “Resurrection” to a final cadence as on the soundtrack, Rózsa overlaps it with the “Epilogue” so there is no break (eliminating the need for the timpani roll that precedes the latter in the theatrical version). He also composed a slightly extended, more elaborate coda for the LP’s “Epilogue.” Throughout this entire album track, the composer’s tempo is swifter than when he recorded it in Hollywood.

Original Soundtrack Alternates and Outtakes

Disc 12, tracks 17–33 present recordings that were made in the original soundtrack sessions for King of Kings but not included on the Rhino 2CD set (by and large because they were not used in the film itself). While most score recordings from this era at M-G-M were made on three-track 35mm magnetic film, King of Kings was made on six-track 35mm “mag”—but for reasons unknown, this score (and the following year’s Mutiny on the Bounty, also done on six-track 35mm mag) suffered from overmodulation (“blow-out” from overly loud recording levels). As on the Rhino 2CD set, every effort has been made to minimize the distortion.

- 17. Prelude (alternate choir)

- On March 21, 1961, Rózsa met with a 40-voice chorus and recorded vocal tracks that were to be mixed in with 19 different orchestral cues. In the end, not all of these vocal tracks were used in the film. This alternate version of the “Prelude” is the same orchestral track used in the film, but the on the choral track the singers are singing “Ah,” rather than the “Hosanna” text ultimately used on the soundtrack.

- 18. Sadness and Joy (alternate)

- In this alternate orchestration, the melody is played by a solo cello one octave higher than on the soundtrack version.

- 19. Mary Magdalene (added choir)/Answer From a Stone

- 20. Christ’s Answer/The Beheading of John (added choir)

- 21. Mount Galilee/The Sermon on the Mount/Love Your Neighbor (added organ)

- 22. The Disciples (added choir)

- 23. Premonitions (added choir)

- 24. Agony in the Garden/Judas’ Kiss (film version—with choir)

- Tracks 19, 20, 22 and 23 are heard here with the choral voices that were recorded but not ultimately used in the film. Track 21 features an organ overlay that was not included in the final film mix for the “Sermon on the Mount” sequence, and track 24 uses the choral track that was included on the soundtrack but is missing from the Rhino version.

- 25. Woman of Sin (early version)

- 26. Woman of Sin (alternate passage #1)

- 27. Woman of Sin (alternate passage #2)

- 28. Woman of Sin (film version)

- Tracks 25–28 present four alternate looks at the “Woman of Sin” cue, in addition to the longest version presented on Rhino disc 1, track 22. The first (track 25) is the original version of “Woman of Sin, Parts 1 and 2” recorded on February 20, 1961. The second and third are inserts recorded at the final session on May 3, featuring a solo cello playing the Virgin Mary’s theme (to which Rózsa adds a short coda for winds on the third track). The final track of this group combines elements of both the original and revised versions as heard in the finished film; it is essentially the same as heard on the Rhino disc, minus the concluding “stately statement of Pilate’s theme” mentioned by Komar.

- 29. Salome’s Dance Part 1 (alternate #1)

- 30. Salome’s Dance Part 1 (alternate #2)

- Here, the opening English horn solo is heard minus the accompanying bassoons, first with tambourine and then without.

- 31. Signal for Pilate

- This unused fanfare was intended to announce Pilate’s arrival at the garrison to meet with Lucius. It is mentioned in Komar’s notes under his discussion of “The Chosen” (Rhino disc 1, track 14).

- 32. Trumpet Signal for Revolt

- 33. Shofar Signal for Revolt (with rehearsal)

- These onscreen fanfares were recorded separately but ultimately mixed with the orchestral track for the cue “Revolt” (Rhino disc 1, track 11). The first (trumpet) calls the Roman troops to battle; the second (shofar) signals the start of the attack by Barabbas and his men. The second is presented in its complete recorded rehearsal and take; Rózsa’s voice can be heard encouraging the player to make certain notes shorter, and then to play one long blast on the instrument.

MGM Records Outtake

Disc 12, track 34 is an early version of the LP’s “The Prayer of Our Lord” featuring a (defective) recording of the choir from Italy that was included on rare early copies of the vinyl. In a letter to Arnold Maxin (president of MGM Records in New York City) dated July 21, 1961, album producer Jesse Kaye wrote: “We had a lot of trouble rehearsing and recording [the Singers of the Roman Basilicas] who learned the English phonetically, and several times, Miki Rózsa and I were ready to abandon the idea of the Italian vocal group because of enunciation.” The first proposed solution was to add about 20 English voices to the already-recorded Rome track, but by the end of the month Kaye realized that poor diction was not the only problem—the version recorded by the Italian choir included an awkward syllabic stress on the word “hallowed” and omitted an entire line of the text (“Thy kingdom come”)! In mid-August, a completely new choral track was laid down in London, and that is the one heard on the album (disc 12, track 11). Fortunately, Rózsa was able to correct the text underlay before the choral octavo was published by Robbins Music. —

From the original MGM Records LP…

In King of Kings, the central figure is the Prince of Peace, and everything centers around Him. In other motion pictures Christ’s face was never seen nor was His voice heard. In King of Kings, we both see and hear Him. The central theme of the music is also, therefore, the theme of Christ the Redeemer, which I have titled the “King of Kings Theme.” It usually appears accompanied by female voices sustaining soft harmonies. The Hebrew themes are fashioned after examples of ancient Babylonian and Yemenite melodies, and the Roman music (as no original Roman music of the period has survived) is my own interpretation of it, the same kind that I established in Quo Vadis, in Julius Caesar and in Ben-Hur. From the musicological point of view, it might not be perfectly authentic; but by using Greco-Roman modes and a spare and primitive harmonization, it tries to evoke in the listener the feeling and impression of antiquity.

Side One

1. King of Kings Theme—Prelude After a short but festive introduction, the “King of Kings Theme” appears as an ecstatic Hosannah. It stresses musically the fundamental idea of the picture which is “Faith and Belief.”

2. The Holy of Holies White-clad priests, the Elders of the Temple of Jerusalem, witness with horror the entrance of the conqueror Pompey on his horse into the Holy of Holies. The somber, Hebraic music expresses the Elders’ tragedy and stubborn belief in their past and in their future.

3. Pontius Pilate’s Arrival Into Jerusalem The new Governor of Judea, son-in-law of the Emperor Tiberius, arrives with his troops in this troubled country. The Roman march, which slowly builds on a monotonous rhythm, attains full peroration as the troops come in sight of the coveted city.

4. The Virgin Mary Joseph the Carpenter and his young wife, Mary, arrive in Bethlehem to be counted. The gentle melody of the oboe, and the undecided, major-minor change of the accompanying harp figure, try to portray musically the gentle character of the Virgin.

5. Nativity A shining star leads the Three Kings Caspar, Balthazar and Melchior, to the humble stable where Mary’s Son Jesus has been born. We hear the voices of angels singing a simple, carol-like lullaby as the Three Kings pay homage and offer their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh to the Heavenly Babe.

6. The Temptation of Christ Many years pass, the Child has grown to manhood and has been baptized in the River Jordan by John the Baptist. Later, upon returning from the River Jordan, He went into the wilderness and stayed there to commune with God and to strengthen Himself for the times to come. Jesus knew the wilderness, its days of heat, its nights of cold and solitude. He ate nothing and hungered. For forty days, He was tempted by the Prince of Darkness, the Devil. As He withstood all temptations, the Devil departed. A weird, twelve-tone theme musically characterizes the Devil, and the scene ends with a strong statement of the triumphant “King of Kings Theme.”

7. John the Baptist was the forerunner of Christ. He prepared himself for his mission by years of self-discipline in the desert before he appeared preaching Repentance. The rite of baptism, which he administered, was a symbol of Repentance. This serene, brooding theme symbolizes his passionate sincerity and self-effacing humility.

8. The Miracles of Christ With the purpose of announcing the advent of God’s Kingdom in the world, Jesus carried on His work. Miraculous deeds followed each other and the number of His followers multiplied day by day. We hear the tortured music thematic of the lame boy, and again the radiant theme of Christ, the “King of Kings,” as He extends His hand over the lame legs of the boy who then begins to walk. A blind man appears; and as the Shadow of Christ touches him, he suddenly realizes that his vision has been restored.

9. Salome’s Dance Herod, the Kind of Judea, is infatuated with his stepdaughter, Salome, daughter of Herodias, his wife. At his birthday banquet, Herod promises her anything if only she will dance for him. The sinuous and sensual, oriental dance begins slowly but gains momentum through the changing rhythmic patterns, growing to an orgiastic and wild finale. Salome’s wish for revenge is fulfilled, and she demands and is presented with the head of John the Baptist, who has publicly denounced her mother.

Side Two

1. Mount Galilee and the Sermon on the Mount A great multitude is thronging to the Mount to hear Jesus speak. This music mirrors their festive spirit of expectancy, and it subsides as Christ delivers the Beatitudes.

2. The Prayer of Our Lord A man from the crowd asks Christ to teach them to pray. We now hear a choral setting of the wondrous words of the Lord’s Prayer.

3. Christ’s Entry Into Jerusalem and Tempest in Judea On the approach of the Feast of Passover, Jesus enters the city on a donkey, among His enthusiastic followers, and goes to the Temple. The accompanying gay, exciting music is based on an ancient Hebrew melody usually sung during the Passover. As He enters the Temple, Barabbas, the murderer, incites the people to storm the Fortress Antonia in an open revolt against the Romans. The Roman archers, however, are waiting for them; and after an arduous battle, they form a human wall, the famous Roman phalanx, and mercilessly mow down the retreating Judeans.

4. The Scourging of Christ The teaching of Jesus and His Messianic claims angered the Pharisees, Sadducees, and the chief priests. Jesus was arrested, tried and condemned to be crucified. Roman soldiers, uninterested, stand around playing dice as the lictor’s flagellum starts to descend upon the frail Body of Jesus. The music emphasizes the dull, rhythmical impulses of this frightful sound which becomes unbearable to Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed Jesus. Judas hears it and faints when he sees the cross and realizes the result of his treachery.

5. The Way of the Cross A somber funeral march accompanies the tragic journey of Christ, carrying His cross, to a place outside the city, named Golgotha. Upon a recurring bass figure, a sad, lugubrious theme rises and falls again as the procession reaches its final destination.

6. Mary at the Sepulcher After Christ commends His spirit to God, His body is taken from the cross by His friends and is laid in a nearby sepulcher. The music expresses the sorrow of the Mother, the tragedy of the Descent from the Cross and of His body being carried to the sepulcher.

7. Resurrection—Finale On the first day of the week which followed, Mary Magdalene finds that the stone which had sealed the sepulcher has been rolled away and the tomb is empty. Later, the Disciples, who are silently collecting their fishing nets by the Sea of Galilee, suddenly look up and hear the Voice of their Master who has overcome death: Christ has risen! We hear, slowly rising, the victorious theme of Christ the Redeemer which culminates in the theme of “The Prayer of Our Lord” and ecstatically closes the picture. —Miklós Rózsa