Madame Bovary

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was the richest and most image-conscious of the Hollywood studios as it reached its 25th anniversary in 1949, boasting a long tradition of “prestige pictures” adapted from classic and semi-classic literature: Ben-Hur, Romeo and Juliet, Anna Karenina, The Good Earth, David Copperfield, A Tale of Two Cities and Pride and Prejudice, among others. Each of these productions was lavishly mounted, with star-studded casts and detailed historical reconstructions. All of them earned a measure of critical and popular success, and yet few endure today as classic cinema—their glossy patina has somehow dulled the sharp edge of the original literary works.

Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1857) has long been judged one of the world’s greatest novels, a landmark for its supremely elegant style, its devastating portrait of the provincial petty bourgeoisie in the age of Napoleon III, and above all its incisive and frighteningly realistic account of a passionate woman trapped by her milieu. Yet in the 90 years since its publication, American filmmakers had not previously adapted this story of a woman whose adulterous passions drag her family to ruin. (Jean Renoir had made a French version in 1933 with Valentine Tessier, and Pola Negri had starred in Gerhard Lamprecht’s 1937 German adaptation.) Hollywood need not have shied from the subject on moral grounds: as in Anna Karenina, the heroine’s adultery is suitably punished by her suicide at the end. But Flaubert’s vision is darker than Tolstoy’s. His concluding death scene is merciless in its clinical precision, and he depicts almost all of the supporting characters as fools or hypocrites—or worse. As George Bluestone pointed out in his influential Novels into Film (1957), a truly faithful adaptation of Madame Bovary would have been an affront to the very consumer society that Hollywood courted as its audience.

The young playwright-scenarist Robert Ardrey assimilated Flaubert’s story in his generally faithful screenplay. (Ardrey, who would later write Khartoum, was also a trained anthropologist whose popular books on human aggression, African Genesis and The Territorial Imperative, gained widespread attention and influenced both Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.) While quite faithful to the novel’s storyline and characters, Ardrey’s script does contain a major invention—one that doubtless helped to “lick” the story for M-G-M: Flaubert himself (played by James Mason) appears on screen to recount Emma Bovary’s history in the context of his trial for “public indecency.” (Such a trial did occur in 1857, although it was actually directed against the newspaper in which the story had been serialized.) This framing device had several advantages for the filmmakers. It helps relate Emma Bovary’s youth in fairly efficient fashion, even if James Mason’s ruefully caressing voice is at odds with Flaubert’s ironic tone. Mason soon disappears from the body of the film, but we return to the courtroom after the final catastrophe to hear Flaubert’s closing argument: “Truth lives forever; men do not.” This summation shifts the tone from tragedy to triumph—a change that seems to have been necessary for M-G-M to undertake a retelling of Flaubert’s grim narrative.

The studio named Vincente Minnelli to direct this important project. The former Broadway stage designer had emerged as the leading metteur en scène of M-G-M’s signature musicals (Cabin in the Sky, Meet Me in St. Louis, The Pirate) and had also succeeded with a modest love story, The Clock, starring his own wife (and M-G-M’s greatest musical star), Judy Garland. Madame Bovary was Minnelli’s first crack at a prestigious literary adaptation. It was a happy encounter. The clash of romantic illusion and harsh reality amid lavish (often French) surroundings would prove to be one of the director’s key themes (An American in Paris, Gigi). Even Judy Garland’s emotional deterioration—the star suffered a breakdown in 1947—may have enhanced her husband’s empathy for Emma Bovary.

Jennifer Jones, loaned out by her domineering husband, David O. Selznick, essayed the tragic lead role with an appropriately unsubtle febrile intensity. She was a fortunate substitution for Metro’s initial choice, the platinum blonde Lana Turner. As Emma’s well-meaning husband, Charles, the studio provided one of its popular leading men, Van Heflin, an actor perhaps too likeable for the role of the cloddish country doctor who frustrates Emma’s romantic desires. Louis Jourdan, another Selznick loan-out, became Emma’s wealthy seducer—a role that helped establish him as Hollywood’s epitome of the romantic Frenchman. (He would play such roles in Minnelli’s Gigi as well as The V.I.P.s.) Amid a capable supporting cast of M-G-M players are such standouts as Gladys Cooper as a protective mother, Gene Lockhart as the pompous pharmacist Homais, and especially Frank Allenby as the cynical moneylender Lheureux. The least familiar name in the cast is Christopher Kent as Léon Dupuis, the provincial law clerk who becomes Emma’s second lover. “Kent” was actually the pseudonymous Swedish actor Alf Kjellin, who had attracted notice in Ingmar Bergman’s very first produced screenplay, Torment (1944), and was making a run at Hollywood stardom. He later returned to Sweden, appeared in other Bergman films, and eventually wound up back in Hollywood acting and directing extensively in series television under his given name.

Released in August 1949, Madame Bovary enjoyed a modest success but received mixed reception from the critics. Only the art direction, obviously guided by the décor-conscious Minnelli, was nominated for an Academy Award. Early reviews were more respectful than enthusiastic, and Novels into Film, a dominant book in early academic film studies, later derided the movie as a prime example of a botched literary adaptation. But as the director’s highly personal body of work (created almost entirely within the restrictive M-G-M studio universe) came into sharper focus over the years, Minnelli achieved considerable status in the auteurist critical pantheon, and his early “prestige picture” has steadily gained in critical esteem.

One reason is the music. Madame Bovary marked Miklós Rózsa’s first major assignment at M-G-M. Rózsa had joined the studio in 1948 at the behest of the executive Louis K. Sidney, the brother of director George Sidney and “one of the kindest and sweetest men I had ever met in the studios.” It was an advantageous contract for Rózsa, who was exempted from some of Metro’s famous “factory system” methods, and it was a considerable coup for a studio whose music department was then less distinguished than those of rivals Fox and Warners. Rózsa would become M-G-M’s star composer for more than a decade, while the songwriter-arranger (and former stockbroker) Johnny Green soon arrived to handle administrative matters and help elevate standards of performance and recording.

From Vincente Minnelli, Rózsa received something he always sought but rarely found in Hollywood: preproduction input from a thoughtful collaborator. This mostly applied to the film’s dramatic centerpiece, the lavish ball at the country château of Vaubyessard, where Emma enjoys a fleeting vision of luxurious romance. Minnelli wanted a “neurotic waltz” for the climax of this sequence, and Rózsa responded with the famous symphonic episode whose intensity explodes far beyond the confines of what any period dance ensemble could have provided. The film (in a bit of dramatic telescoping) introduces Emma’s seducer, Rodolphe Boulanger, into this sequence, and the intoxicating waltz later becomes the leitmotiv for Emma’s doomed attraction to the cynical country squire. Rózsa must have liked this piece, for he used a scaled-down version as background music in several later M-G-M productions, including: The Story of Three Loves, Valley of the Kings, The Seventh Sin and Tip on a Dead Jockey.

While the achievement of Minnelli and Rózsa possesses considerable dramatic power, it can be argued that their romantic approach is at odds with Flaubert’s detached irony. This is nowhere more apparent than at Emma’s death. Flaubert has his heroine coughing up black blood while a blind passerby chants a bawdy song in the street below. Minnelli considerably softens the impact of the terrible suicide by offering a moment of tender penance and repose, abetted by Rózsa’s gentle and quasi-religious scoring (akin to a scene in the later Quo Vadis). No matter. The film ultimately stands on its own as a flawed but still powerful expression of the conflicted romantic imagination.

The score was pivotal in Miklós Rózsa’s career. It stands at the juncture between the gritty black-and-white film noirs of the 1940s, where the musical style approximates his hard-hitting, Hungarian-inflected concert music, and the Technicolor historical-biblical romances of the following decade, where his brilliant musical palette and songful lyricism were soon to find freer expression. The music of Madame Bovary has long been popular. Exceptional for the period, a short suite was extracted from the soundtracks for release on 78s. This seems to have been the very first commercial issue of actual dramatic film music tracks. It later appeared on LP, together with music from Ivanhoe and Plymouth Adventure. The waltz has had numerous subsequent recordings and has become a staple of “live with film” concerts, where it never fails to bring cheers. Elmer Bernstein’s 1978 version of highlights from Madame Bovary with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra was one of the last productions in his celebrated Film Music Collection series (reissued on CD as FSM Box 01). Now, after 60 years, FSM has been able to combine all surviving music-only cues (from ¼″ masters of what were originally 35mm optical film rolls) with music-and-effects tracks for the remainder of the score (such cues are denoted below with an asterisk) to present the full original soundtrack of this classic score for the first time. Some source cues and alternates are included in a bonus section, while additional source cues, alternates and pre-recordings can be found on disc 11 of this box set. Listeners who find the music-and-effects tracks distracting can hear the music-only score tracks by programming tracks: 1, 2, 4, 8, 10, 12, 15, 17, 21, 24, 32 and 26.

- 1. Main Title

- With the urgency of a dark, suppressed passion, Rózsa launches directly into his evocative, churning theme for Emma Bovary’s eternal longing. Christopher Palmer, in his liner notes for Elmer Bernstein’s 1978 recording of the score, observed:

During the mid- and late 1940s Rózsa’s main preoccupation had been with psychological melodramas and gangster thrillers, and something of the edge of his style as sharpened to this purpose is preserved in odd corners in Madame Bovary (notably in the harmonic asperity of the [“Main Title”]). But the emphasis now is veering to richness of texture and lyrical expressiveness and above all to an all-pervading humanity, warmth and compassion—qualities which are as essential a part of the man as they are of his music.

- The main title melody rises and falls as if in tragic summation of a lifetime’s romantic yearning. Palmer continues: “[A] note of impassioned desperation is also struck, representing Emma’s striving for the hopelessly unattainable.” Note how the central section, with its insistent sequence of descending sevenths that never quite manage to resolve to a full octave, will become a second theme for Emma’s frustration.

- 2. Charles in Love

- The film begins with the 1857 trial of the author Gustave Flaubert (James Mason), seen in the dock of a Paris courtroom accused of obscenity in his novel Madame Bovary. While testifying, Flaubert begins to relate the story of the novel: a country doctor, Charles Bovary (Van Heflin), makes a house call to a Norman farm and is smitten with his patient’s beautiful daughter, Emma Rouault (Jennifer Jones). Rózsa’s gorgeous, gently romantic cue, with prominent solos for glowing clarinet and flute, is based on a French folk song. The theme, labeled “Romance” on the film’s cue sheet, underscores the first conversation between Charles and Emma.

- 3. Retrospection*

- The “Romance” theme continues, now on a pastoral oboe, as Emma is filled with delight after Charles’s departure, segueing to her main theme while Flaubert narrates about the source of Emma’s romantic dreams: images from popular culture that have filled her with unrealistic aspirations.

- Ave Maria*

- Flaubert flashes back to Emma’s unhappy years at a convent, where she practices piano scales and pines away while her fellow students sing a Gregorian “Ave Maria” in chapel.

- I Knew a Love*

- Emma and the other girls at the convent listen, enraptured, to a Swiss seamstress who sings “the love songs of the last century,” further inspiring Emma with unfulfillable yearnings. This is another traditional French folk tune, with the arrangement credited to Rózsa and William Katz.

- 4. Dreams

- Flaubert tells of Emma’s convent and post-convent years immersed in romantic novels. Rózsa gently weaves the melody of “I Knew a Love” (with initial viola solo) into his poetic and humane tapestry for the young woman’s ambitions. Strings give way to oboe as one of Rózsa’s typical pastoral tunes marks Emma’s return to the farm. Her own theme (strings again) returns for a vision of faraway clouds, the intensity of the music telling us of Emma’s pent-up emotions. As the flashback ends, Emma awaits the next visit of Charles Bovary, whose “Romance” theme (followed by yet another folk-like melody) returns as Charles rides to the town of Yonville, planning a future there.

- 5. Charles Proposes*

- Charles proposes marriage to Emma, who is deliriously happy—ignoring his warnings that he is an ordinary, unexciting man. Rózsa’s score surges and drifts on the happy currents of the “Romance” theme.

- 6. Arrival in Yonville*

- Charles and Emma are married, quickly fleeing their rustic wedding party. They arrive that night at Yonville, where he is to become the town doctor. After an initial reference to the (still popular) 17th-century tune “Auprès de ma blonde” (“Beside My Sweetheart”), the music blossoms into Rózsa’s tranquil, dreamy strains for Emma’s rapture: “It’s like a picture in a storybook.”

- 7. Honeymoon*

- The “Romance” theme soars as Charles carries Emma across the bridal threshold. But—tellingly—the musical climax of this cue (feverish repetitions of the first phrase) is reserved for the morning after, as the frustrated bride suddenly resolves to beautify her surroundings. In between, Emma’s theme accompanies her fretful wakefulness and her throwing open the shutters in near panic. Charles awakens (the “Romance” theme returning) as Emma pledges to make their home the finest in Yonville.

- The next music in the film is Emma’s brief piano performance at a party of Chopin’s Waltz in A minor, Op. 34, No. 2 (played on the soundtrack by a young André Previn); the recording no longer survives (see disc 11, track 22).

- 8. New Dreams

- Humiliated at the party by the condescension of the visiting Marquis d’Andervilliers (Paul Cavanaugh), Emma is overtaken by a terrible disillusionment with her woman’s lot in a provincial town. Her mood receives a new theme, derived from the midsection of the “Main Title” and introduced here by English horn. She tells a consoling Charles that she wants to have a son, who would not be so restricted in life; the cycle of Emma’s emotions continues as the main theme accompanies a pan to the romance illustrations on her wall, seen earlier in “Retrospection” (track 3). The film cuts ahead to the birth of Emma and Charles’s child—a daughter—given a charming, nursery-style theme.

- Disillusion

- The “baby” theme (at 2:20) bridges another ellipsis as young Berthe Bovary is now a toddler. But as Emma looks out her window and sarcastically describes the tiresome routine of provincial life, the “Disillusionment” theme forms a dirgelike accompaniment, with a nervous accompanying harp figure complementing the tolling of the village clock “to announce the death of another hour.” Charles is unable to offer solace, but an unexpected invitation to a ball at the château of the Marquis pricks Emma’s interest. (In the film, the heavy, ominous chords at the end of this cue are barely audible under Charles’s words.)

- 9. Passepied/The Marquis’s Quadrille/The Gay Sixties—Polka/L’Hirondelle—Galop*

- Charles and Emma attend the ball. A brilliant Minnellian montage contrasts Emma’s deepening enchantment with Charles’s utter befuddlement. Visual as well as aural frissons abound, as in the polka, where the violins cover a cut from the gentlemen smashing their drinking glasses to a woman’s fan sweeping against a crystal chandelier. A succession of source cues (original with Rózsa) play throughout the night. Palmer notes: “Rózsa’s talent for recreating the essential spirit (as opposed to the strict letter) of popular music both old and new is called into play here with treasurable results.” These dances exemplify the growing mastery of period pastiche that would characterize Rózsa’s many historical scores of the 1950s. Interestingly, the November 1948 pre-recordings for the dance scenes used existing music, including the “Bitte Schön! Polka Française” and “Banditen Galop” by Johann Strauss Jr., as well as Rózsa’s own waltz (see disc 11, tracks 24–26). André Previn and Mel Powell were the rehearsal pianists. Evidently the players danced to Strauss, and then Rózsa scored the entire sequence with his own music after it had been staged and edited.

- 10. Madame Bovary Waltz

- The climax of the ball—and one of the finest set pieces in the careers of both Rózsa and director Minnelli—is the glorious waltz to which Emma dances with the handsome aristocrat Rodolphe Boulanger (Louis Jourdan). Palmer writes:

This elaborately choreographed sequence, in which Emma is literally swept off her feet by Rodolphe, is the most spectacular set piece in the film, action, camera and music being fused and interpenetrated in masterly fashion. This was possible only inasmuch as the music was written first, recorded in a temporary version for two pianos, and the action planned and shot in accordance with the music—precisely the routine of a choreographic sequence in a musical, at the negotiating of which Minnelli was of course an old and practiced hand. The music begins in what is ostensibly a formally elegant vein, but the orchestration already has an unnatural flush to it and the contours of the main theme are unusually wide-spanned. Little by little the momentum increases as Emma and Rodolphe become gradually oblivious of all the other dancers, the two main strains of the waltz being submitted to Rózsa’s customary balance between symphonic development and varied repetition. A simple but telling modulation [at 2:40], which has the effect of the ground giving way underfoot, marks the real turning-point, and from now on the music accumulates, not a savage hysteria as in Ravel’s La Valse, but a reckless, intoxicated, all-submerging ecstasy. The air grows so hot that all the windows in the ballroom are broken, but still the dance swirls madly on, sempre accelerando, to reach a fever-pitch of excitement and one which frequently provokes a spontaneous outburst of applause when the film is screened.

- Here we present the “Madame Bovary Waltz” as slightly edited for the MGM Records release (but correcting an anomaly of the LP in which an overlap failed to join two sections; this was because on the original 78 rpm release, the piece had to be split across two sides).

- 11. Temptation (Torment)*

- As Emma returns to her daily routine—packing away her dress from the ball—the waltz melody lingers in a ghostly flute solo, segueing to Emma’s theme as she again views her gallery of romantic illustrations. When young legal clerk Léon Dupuis (Alf Kjellin, credited as Christopher Kent) visits the house, she tries to initiate an affair; lush, shimmering textures precede a new romantic theme for their relationship, reminding us that luxury and romance are inextricably enmeshed in Emma’s mind. Léon’s theme dissipates into ineffectual fragments as his domineering mother pays an inconvenient visit.

- 12. Crossroads

- Emma wants Charles to operate on the clubfoot of the town simpleton, Hyppolite (Harry Morgan, appearing as Henry Morgan), thinking that such an advanced surgical success will elevate Charles’s standing and solve her romantic yearning. He initially refuses, knowing his limitations as a physician, and is startled by her anguished reply: “Do you want me to love you or don’t you?” The main theme surges—subsiding into dour tones—as Charles is overcome by the gravity of his wife’s despair. He resolves to operate.

- 13. The Operation*

- Charles cancels the surgery at the last moment: his decency will not allow him to risk harming Hyppolite. (In the novel, Charles botches the operation and leaves Hyppolite with a putrefying wound that haunts the remainder of the story. The filmmakers’ change ennobles Van Heflin’s movie character, but it also sabotages Emma’s motivation, rendering her disgust less explicable.) A grim ostinato accompanies the surgical preparations (echoing the triplet harp figure of Emma’s frustration) and Charles’s pained withdrawal, ending when he slams the door on a dejected Emma. Palmer notes: “The first part of this sequence—the start of the operation and Emma’s despairing reaction when she learns that Charles has not performed it—is based on an ostinato-like rhythmic motif established in the bass in the first bar.”

- The second part of the cue (at 1:49) accompanies Emma joining Rodolphe for a horseback ride in the country, while the music soars into a passionate rendering of the waltz theme as the camera tactfully turns aside from their tryst.

- 14. Remorse*

- Charles interrogates Emma upon her return. Low-key suspense music accompanies their marital discord, including a poignant rendition of the “Romance” theme as Charles expresses genuine concern for his wife’s happiness: “I love you so much.” But the cue ends with a wistful rendition of the waltz theme as Emma, alone, regards her reflection in a mirror, signaling her romantic preoccupation with Rodolphe—and with herself.

- 15. Rodolphe’s Love

- This remarkable and lengthy cue appears under dialogue as Emma luxuriates with Rodolphe at his country home. The music, as much as the words, dramatizes the course of their affair. An extraordinarily beautiful new theme suggests the tenderness of their romance (legato) and also the darker mood of Rodolphe’s bachelor resistance (marcato). Frequently interrupting is the waltz theme of Emma’s insatiable passion. It makes a particularly dramatic appearance after Rodolphe throws souvenirs of past loves into the fireplace, and again at the end of the track, as the couple rendezvous for another horseback ride.

- 16. Emma’s Love*

- Emma and Rodolphe speak in the woods about plans to elope. Their love theme plays softly, with an interlude of the main theme as Rodolphe reminds Emma that they would be forced to abandon her daughter: “This is where dreams leave off, Emma.”

- 17. Coach

- One of the most dramatic cues in the score is for Rodolphe’s cruel rejection of Emma, crafted with new thematic material by Rózsa. (See the Elmer Bernstein Film Music Collection liner notes for illustrated musical examples of the two new motives for this sequence.) Palmer writes:

Emma persuades Rodolphe to elope with her; the plan is that his coach will stop in Yonville to collect her at dead of night. The coach arrives but drives straight through, with predictably devastating effect on Emma. This superb dramatic sequence is beautifully constructed musically: the first motif is presented in somber quasi-Hindemithian fugal style, the second almost incidentally as part of a poignant passage for string quartet (Emma in the nursery). But, once it is established, this second motif gradually becomes an idée fixe as the scene darkens and Emma’s mood becomes one of nervous anticipation (violas and muted horns). Ultimately [the second motif] as an ostinato becomes identified with the sound of horses’ hooves in the distance; as the coach draws ever nearer the two motifs—the one rhythmic, the other melodic—are united and drive the music to a shattering climax. In the final bars [the first motif] voices Emma’s overwhelming despair.

- The Letter

- Emma returns home, where Charles waits, disapproving and heartbroken. In a basket of fruit, Rodolphe has left a farewell letter that devastates Emma when she reads it. Charles restrains her from throwing herself out a window. Rózsa’s Sturm und Drang cue continues the first motive from “Coach” as Charles tries to console the delirious Emma. Softer textures accompany Charles burning the letter in an attempt to soothe Emma, but she is practically catatonic.

- 18. Recovered*

- Flaubert narrates how Emma recovered in the subsequent months. The main theme plays softly for the passage of time, followed by the “Romance” theme, as Charles has not given up on her.

- 19. Emma’s Dream Waltz*

- Charles and Emma reconnect at the opera with Léon Dupuis, now a lawyer, and Emma concocts an excuse to see Léon apart from Charles. Filled with renewed longing, Emma reenacts in her hotel room the waltz that accompanied her first dance with Rodolphe, here given a spectral, hypnotic reprise by Rózsa—but the final chord is dissonant, as she suddenly sees herself in a broken mirror amid shabby surroundings.

- 20. Léon’s Love*

- Intending to abandon her affair with Léon, Emma finds herself swept up in his arms. Fragments of their theme mirror Emma’s frustration and indecision before the pathetically beautiful melody blossoms anew for their kiss.

- 21. Last Day with Léon

- The plot thickens with Charles’s father dying, leaving Charles the family estate. With debts mounting and a crisis impending, Emma needs money to pay off a predatory moneylender, Lheureux (Frank Allenby), whose previous scenes have played without music. She turns to Léon, hoping to extort money from Charles’s estate. Rózsa’s cue underscores a dialogue scene during Léon and Emma’s last day before she must return to Yonville, including the “Disillusionment” theme as Léon reports that the estate is worthless. Woodwinds pipe happier strains as the couple elect to enjoy their remaining time together.

- 22. Lheureux’s Walk*

- Suddenly the malevolent Lheureux spies the lovers in Rouen and in a montage given frightening force by Rózsa’s music, seems to walk directly to the Bovary home in Yonville, his footsteps striking fear into Emma’s heart. Palmer: “The music builds steadily on a four-bar bass ostinato timed to the relentless rhythm of his footsteps.”

- 23. New Blows*

- Lheureux has sold the Bovarys’ debts to Guillaumin (Henri Letondal), and when Emma pleads for leniency from him, she is horrified that he apparently seeks sexual favors. She slaps him and storms out, her rage captured by Rózsa’s tumultuous cue.

- Despair*

- The dirgelike theme from “Coach” returns as Emma is beset by problems: she turns to Léon for money, but he confesses he is a poor law clerk, not the successful lawyer he had claimed to be. Even the recurring image of her mirrored reflection seems to be betraying her, as she applies heavy makeup to improve her appearance; finally, she travels to make a desperate appeal to Rodolphe.

- 24. Humiliation

- Rodolphe, surrounded by luxury, claims to have no money to lend to her. As he rebuffs her desperate seduction, the music echoes the harsh rhythms of “The Operation.” More orchestral turmoil plays under Emma’s despair, including a rueful, solemn statement of the main theme as she explains that, had their positions been reversed, she would have done anything to help him—a noble side of her romantic obsession.

- 25. Suicide/Arsenic*

- Emma steals into an apothecary shop and ingests poison. The new theme heard here is by turns ominous (clarinets for the dark storeroom), then grim (low strings as Emma, in Flaubert’s words, “ate greedily”), and then tender (violins) for pitiful last confrontations with husband and child: “Please don’t hate me now.” Churning strains follow as the apothecary brings word to the dumbfounded Charles: “Arsenic!”

- Agony

- Charles consoles Emma on her deathbed, accompanied by a new, dour melody that Palmer labels the “death-agony” theme:

The music follows her deathbed agony in compassionate detail. Halfway through, just before the [English horn] enters with the “death-agony” theme, harp and violas establish a pulse-like repeated note ostinato which persists to the end. Charles’s theme is heard in a solo violin as he declares his love for his wife despite all that has happened, and the music sinks resignedly to rest with Emma’s theme of world-weariness.

- Holy Unction

- Evocative strings—heavenly, yet mournful (anticipating Rózsa’s 1951 Quo Vadis)—accompany a priest attending to Emma’s last rites. Solemn chords accompany tolling of the village clock. The score touches retrospectively on the three love themes (the waltz, Léon’s theme and the “Romance” theme for Charles) as Flaubert’s narration comments on the lives Emma had touched.

- 26. Finale

- Flaubert’s courtroom summation is a defense of artistic truth. As his image freezes, a scrolling text testifies to his acquittal and to the immortality of his masterpiece, which “became a part of our heritage, to live—like truth itself—forever.” Over this sententious text and the ensuing cast list comes a final recapitulation of the “Main Title,” its solemn bass line now embellished with a trumpet solo and a final blaze of brass and percussion. The survival of two microphone angles has allowed this closing track to be presented in stereo.

Bonus Tracks

- 27. Anniversary Fanfare #2/Main Title

- The “Main Title” is here preceded by Rózsa’s “Anniversary Fanfare #2,” which accompanied a title card on 1949 M-G-M films in celebration of the studio’s 25th anniversary.

- 28. Charles in Love (alternate)

- This is an unused version of track 2, recorded “wild” (not in synchronization to picture) and featuring a formal ending.

- 29. Chanson Populaire*

- This raucous country tune (presumably a folksong) is sung by the drunken country folk at Charles’s and Emma’s wedding. (The cue sheet specifies three male voices and ten “girls,” plus accordion and fiddle.)

- 30. Le Joli Tambour*

- Emma’s romantic waltz partner, local squire Rodolphe Boulanger, seduces the all-too-willing Emma during a tiresome agricultural show. Rózsa arranged this band version of the French folk song “Le Joli Tambour” (“The Pretty Drummer Boy”) as source music.

- 31. Recovered/Lucia di Lammermoor*

- Charles escorts Emma to the opera in Rouen in an attempt to lift her spirits. Tenor Gene Curtisinger and soprano Mary Jane Smith recorded the studio vocals for the onscreen performance of the “Duet Finale” from the end of Act One of Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor; this is followed by a short passage from the opening of Act Two, where Curtisinger is joined by baritone Robert Brink. The excerpts are sung in Italian, even though a poster in the film reads Lucie de Lammermoor and a historically accurate performance would have been in French. The opera sequence is preceded here by the cue “Recovered” (track 18) as it is in the film.

- 32. Agony/Holy Unction

- This music-only track is heard here separated from the music and effects version of “Suicide/Arsenic,” which precedes it in the complete score sequence (track 24) presented earlier.

Disc Eleven

- 18. Prelude/Romance

- This combination of the “Main Title” and “Charles in Love” appeared as the first side of the 2-disc 78 rpm soundtrack album later issued on a 12″ LP (along with tracks from Ivanhoe and Plymouth Adventure). The “Main Title” is an alternate take from that used in the film (disc 1, tracks 1 and 27); “Charles in Love” is a combination of the film take (disc 1, track 2) with the extended ending of the alternate (disc 1, track 28).

- 19. Torment/Passepied

- “Torment” is the second half of the cue entitled “Temptation” in the film (see disc 1, track 11); this is a “wild” take used only on the record album. It was combined with the complete “Passepied” (only the first part of which is heard in the film) on the MGM Records release (side 2 of the 78 rpm album). These are the only surviving music-only masters for these cues.

- 20. Emma’s Waltz (2nd pre-recording)

- The third and fourth sides of that 78 rpm album featured the “Madame Bovary Waltz,” which has already been presented in this box set (disc 1, track 10). In lieu of that fully orchestrated version, this track is a “pre-recording” of the piece for two pianos, created to aid in choreographing and filming the scene. There were actually two such recordings made, both performed on two pianos by Mel Powell and André Previn. This second one was recorded on February 23, 1949, about six weeks before the orchestral version was recorded on April 4, and is thus one step closer to the music’s final form. In this arrangement, the introduction has become the one heard in the film, and the opening melody has assumed its familiar shape.

- 21. Ave Maria (pre-recording)

- Soprano Anne Marie Biggs recorded this unaccompanied solo version of the traditional Gregorian chant on March 3, 1949. In the film, it is sung by a small choir of 10 female voices (see disc 1, track 3).

- 22. Mazurka in F-sharp Minor (pre-recording)

- This Chopin piece, performed by André Previn, was set down on that first day of pre-recordings in November 1948 but was eventually replaced by a Chopin waltz recorded the following January. The latter recording, sadly, no longer survives except in the film.

- 23. Trianon (pre-recording)

- This salon trifle by pianist Aimé Lachaume (1871–1944) was also recorded by Previn, presumably for the same scene in which Emma plays at a party.

- 24. Bitte Schöne Polka (pre-recording)

- This track and the next are pieces by Johann Strauss Jr. arranged for two pianos, again played by Powell and Previn. Although presumably used to help in the filming of the ball sequence, they were eventually replaced by Rózsa’s own period orchestral pastiche (disc 1, track 9).

- 25. Banditen Galop (pre-recording)

- See track 24, above.

- 26. Emma’s Waltz (1st pre-recording)

- This initial version of the famous waltz was the very first pre-recording made for the film (on November 20, 1948). It is of special interest because of the slightly different, less-ornamented version of the opening melody.

- 27. French Medley

- This medley of French folk music is heard (at a very low level in the finished film) as outdoor source music from the agricultural show as Rodolphe seduces Emma in a secluded room (before “Crossroads,” track 12). The scene is the closest the movie comes to rendering Flaubert’s ironic tone. As the lovers embrace, we hear the mayor addressing the crowd outside: “And now we ask for manure. We demand manure!”

- 28. Holy Unction

- This cue from near the end of the film (see disc 1, tracks 24 and 31) is heard here in a version recorded for use in The Red Danube (see disc 2, track 6).

- 29. Madame Bovary Waltz

- In what probably became something of an “in-joke” within the M-G-M music department, Rózsa recycled his Bovary waltz numerous times when he needed a romantic source cue in other films. This unused arrangement for string quartet and piano was recorded for Valley of the Kings but replaced by a longer, faster version in the film (see track 15 of FSM Vol. 7, No. 17). —

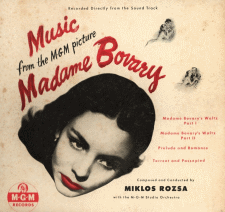

Five selections from the soundtrack of Madame Bovary were released on a 2-disc 78 rpm album by MGM Records (MGM-43) in 1949. All of them can be found in this box set: “Prelude” and “Romance” (disc 11, track 18), “Torment” and “Passepied” (disc 11, track 19) and the “Madame Bovary Waltz” (disc 1, track 10). In 1957, MGM Records reissued these same selections on a 12″ LP (E3507ST) combined with soundtrack cues from Ivanhoe and Plymouth Adventure (which had initially been issued together on a 10″ LP in 1952, MGM Records E179). Polydor reissued this LP in the U.K. in 1974 (MGM Select 2353 095).

From the original MGM Records LP…

Music Recorded Directly From the Sound Tracks of the M-G-M Motion Pictures

Music Composed by Miklós Rózsa

M-G-M Studio Orchestra Conducted by Miklós Rózsa

MGM Records E3507ST

About Miklós Rózsa

Miklós Rózsa was born in Budapest, Hungary. Precocious musically as a child, he was quite advanced

in the study of the violin by the time he was five. Later, he mastered the viola and the piano. He reportedly made a

first attempt at composition at the age of eight. After completing schooling in his native Hungary, he travelled

to Germany for four years of intensive musical study in composition and musicology at the Leipzig Conservatory.

By 1929, his music began to appear with a certain frequency before the public. Such works as his

North Hungarian Peasant Songs and Dances, Op. 5 (1929), Serenade for Small Orchestra, Op. 10 (1932),

and Theme, Variations and Finale, Op. 13 (1933) spread his name throughout Europe. His

Capriccio, pastorale e danza, Op. 14 created something of a sensation in its first performance at the

Baden-Baden Festival in 1939 and secured Rózsa’s position on both sides of the Atlantic. During the

’30s, the composer chiefly divided his time between Paris and London, composing much ballet and film music in

addition to his normal activities in symphonic and chamber music. He came to America in 1940 and settled in Hollywood,

California. Here, he has divided his creative activities between music for movies and music for concert performance and

has also taught composition at the University of Southern California. His movie credits are many and distinguished.

He is considered in many circles one of the most important of the serious composers who have brought maturity to the

field of motion pictures. His film scores have the rare quality of serving well and even of psychologizing screen

action in a singularly apt fashion and yet of having such solid musical merit that the music might be approached apart

from film and yield a listening experience of value. Two prime examples of this dual nature of

Rózsa’s film music, apart from the three film suites presented in this recording, might be found in his

exquisite score for Jungle Book and his exciting music for Quo Vadis, both of which have

yielded concert scores of excellence. Among his most notable concert scores created apart from films in recent years

is the much-hailed Concerto for Violin and Orchestra composed expressly for Jascha Heifetz.

Other of his well-remembered motion picture scores include those for Spellbound, A Double Life, The Thief of Baghdad, The Lost Weekend and The Barretts of Wimpole Street. [Note: Rózsa did not score The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1957)—Bronislau Kaper did. It is possible that Rózsa was scheduled to score it at the time the LP was produced.]

About the Music for Ivanhoe

Sir Walter Scott’s classic Ivanhoe was long the despair of movie-makers because, while it contained all

of the ingredients of which great films are made, the length and complexities of the plot seemed an insurmountable

barrier in the job of translation to the screen. However, after years of research and many trial screenplays,

producer Pandro S. Berman and director Richard Thorpe felt they had the makings of a great picture, and

M-G-M started production almost immediately in the Ivanhoe country of England.

The film itself was—and, through its definite classic quality is—testimony that their fondest hopes

were realized in a motion picture of startling brilliance, scholarly authenticity and thrilling entertainment.

Not a small part of the success of Ivanhoe was due to the music of Miklós Rózsa. For the film, Dr. Rózsa had the dual task of establishing a mood which would reflect the archaic atmosphere of the story while evoking the emotions of an audience accustomed to music of much greater scope than that of England during the Crusades. A discussion of the technical aspects of this problem is out of place here; it is sufficient to say that the music is essentially that of a 20th century composer inspired by thematic material of the 12th century, and using modern instruments to reproduce the sound and—more important—the feeling of that period. The sections of the Ivanhoe suite recorded here are as follows:

Prelude The heroic stature of the film is established immediately by the opening fanfares, musically foretelling the color and excitement of knights in gold and scarlet armour, lovely women in flowing gowns, and stern castles set high on granite-walled heights. The triumphant theme of Ivanhoe (Robert Taylor) is heard, followed by the melody of the ancient ballad of Richard the Lion Hearted. Then we hear the military theme of the Norman knights who rule a rebellious England while King Richard is held for ransom in far-off Austria.

The Lady Rowena This musical expression of Rowena’s (Joan Fontaine) abiding love for Sir Ivanhoe is full of tenderness and compassion. The music portrays a woman sensitive enough to give up the man she loves in order to save his life.

The Battle of Torquilstone Castle Visually the most exciting sequence of the film, the ferocious Saxon assault on Torquilstone Castle becomes a musical interweaving of the themes of the attacking Saxons and the defending Normans. First, the challenge of Robin Hood of Locksley is heard, and then the answering scorn of De Bois-Guilbert (George Sanders). Then, Ivanhoe, held prisoner in the castle shouts “In the name of Richard, attack and wipe them out!” At this command, the air is filled with the twang of Saxon arrows and the siege begins. A sally of Norman knights is driven back into the castle by invincible long-bows and the Saxons advance inch by inch to the foot of the granite walls. Ivanhoe, meanwhile, turns on his captors and starts a fire within the fortress. To the melee of battle and the clashing themes of Saxon and Norman is added the flaming music of an inferno roaring through the castle. At last the great gate of the barbican is splintered by a battering ram, the castle is taken, and Ivanhoe delivered.

Rebecca’s Love The daughter of Isaac of York, Rebecca (Elizabeth Taylor), has fallen hopelessly in love with Sir Ivanhoe although she knows that she can never marry him. When Ivanhoe is sorely wounded, Rebecca nurses him back to health. While he is still unconscious, Rebecca silently declares her love for him, and this passionate music expresses her heart’s desire.

Finale Perhaps the most stirring ending to any film, the finale of Ivanhoe brings the rescued Richard to England just in time to see Ivanhoe deliver the death-blow to De Bois-Guilbert. The music of this episode varies in mood from the clash of the battle-axe against chain-mail to the tender farewell of Ivanhoe and Rebecca; from the heraldic entrance of Richard and his Crusader-Knights to the death-scene of De Bois-Guilbert. The last bars repeat the heroic theme of the prelude, as fanfares greet the triumphant king and his rescuer, Sir Wilfred of Ivanhoe.

About the Music for Plymouth Adventure

Plymouth Adventure was the motion picture telling of the story of a group of almost-ordinary people

caught up into an epic adventure. Brought to life from the dry accounts of history books, here was presented the

Pilgrims as they were driven out of England—and the sailors who brought them to the New World in the tiny

Mayflower. Producer Dore Schary and director Clarence Brown made their film a film about people –the weak

and the strong, the good and the godless—who left Southampton Harbor in August of 1620 to plant a seed that

blossomed into the greatest nation on the earth.

Miklós Rózsa’s music is therefore primarily a music of personalities, reflecting, as did the film itself, the people who made this bit of history. Nothing could be more personal or more authentic than the music book which the Pilgrims took with them across the sea. Henry Ainsworth’s Psalter, published in Amsterdam in 1612, contained the Pilgrim’s only music, and is the inspiration of the opening hymn heard in the Prelude. The sections of the Plymouth Adventure suite recorded here are as follows:

Prelude The film opened with a spoken foreword as the screen filled with the Mayflower under full canvas, breasting the waves as she sails toward freedom. We hear the chorus in “Confess Jehovah, Thankfully!”—a hymn from Ainsworth’s Psalter, breathing the spirit of adventure and the indomitable strength of the faithful.

John Alden and Priscilla John Alden (Van Johnson) has signed on as carpenter to the company of Pilgrims, and aboard ship he sees young Priscilla (Dawn Addams). A gentle romance is born of this meeting to culminate with their marriage in the New World. The music is tender and romantic, with the twinkling sound of a harpsichord evoking their young love. The sequence ends with a lively theme, reflecting the joyous expectations of a new and happy home for the emigrants.

The Passion of Christopher Jones The hardened and cynical skipper of the Mayflower, Christopher Jones (Spencer Tracy), sees in Dorothy Bradford (Gene Tierney) a woman of great beauty and strange attraction. He knows that she will never leave her husband (Leo Genn), but knows just as surely that she returns his love. This dark and brooding music, reminiscent of the English melodies of the 17th century, emphasizes the intensity of the Captain’s distraught love for a woman he can never have.

The Mayflower Actually an expansion of the theme first heard in the prelude, this music is that of the ship itself, rather than of its people. We hear strong bass chords as the sails are hoisted, hopeful clarion trumpets as the top-gallants fill with outward breeze, and lyric strings as the Mayflower gallantly sails Westward. As the ship gets under way, the full theme is heard, joyously recapitulating the opening hymn.

Dorothy’s Decision Dorothy Bradford realizes that she does indeed love Jones, but her stern duty is toward her husband. Trying to find a way out of this untenable situation, she stares out at the fathomless sea—music is heard, passionate and dramatic, imbued with the lyricism of her love and the brooding of her conscience.

Plymouth Rock It is dawn. The sun comes over the horizon, and we see the Mayflower from our vantage point on Plymouth Rock. She is setting sail for England, but the Pilgrims are staying in their new world to carve out a free, new nation. Christopher Jones, now a better man for his experiences, fires a last salute “for the living…and the dead.” and the sound of the gun is drowned out by the strain of “Confess Jehovah, Thankfully!”

About the Music for Madame Bovary

The thrilling music from the film Madame Bovary, so important a part of the enchanting screen adaptation

of the classic novel by Gustave Flaubert, is in itself superb entertainment. The score is one of

Miklós Rózsa’s most distinguished and this recorded suite recreates it vividly. The sections of

the suite are as follows:

Madame Bovary’s Waltz The heroine’s waltz is described memorably in Flaubert’s book. She is swept into it by the aristocratic and arrogant Rodolphe (Louis Jourdan), who is to play such an important part in her downfall. The Waltz builds to a wild ecstasy in her mind, amounting almost to delirium. The room and the chandeliers seem to whirl about her; she feels faint; the servants smash the heavy windows for air, and suddenly this happiness is snatched away from her by the drunken behavior of her husband. She rushes from the ballroom disillusioned and disgraced.

Prelude This section introduces musically the complex character of the heroine of Flaubert’s novel, Emma Bovary (Jennifer Jones). It suggests the turbulent and contrasting emotions always at war within her, from innocent dreams to sordid passions, which have made her through the years one of the most controversial and haunting women in all fiction.

Romance An old French folk song provides the basis for this section and mirrors the devoted love of Charles Bovary (Van Helfin) for Emma, the one love that through their marriage and until her death remains the only loyal and unselfish love she is to know.

Torment This section depicts Emma’s first inner conflict that throws her into the arms of Léon Dupuis (Christopher Kent). This theme reoccurs throughout their illicit love affair.

Passepied This stately dance in the style of the 18th century opens the ball at Vaubiessard, the one night in Emma’s life when reality seems to meet her dreams.

From the Polydor reissue LP…

MGM Select 2353 095

Miklós Rózsa began his film career in London as a member of the music department of Sir Alexander Korda’s London Film Productions. On settling in Hollywood he worked variously for Paramount, Universal and other studios before signing a contract with M-G-M in 1948. This was a major turning point in his career, as much from the purely musical point of view as from any other. For during the mid and late ’40s his film music idiom had been approaching his concert style more and more closely, largely because the raw primitivism of his Hungarian folkdance-derived rhythms had lent itself extraordinarily well to depiction of the American underworld in films such as The Killers, Brute Force, The Naked City and Criss Cross. But then in 1949 came Madame Bovary, to unleash the full flood of a romanticism which had always been endemic of Rózsa’s mature style, and pointed the way to that fine series of historical romances, pageants and epic spectaculars which have won for the composer his widest and most appreciative audience. Three of these are represented on this record.

First, the pivotal Madame Bovary. Vincente Minnelli directed Jennifer Jones in the title role and James Mason as the author (more heard than seen) with excellent support from Van Heflin as the long-suffering country doctor, Louis Jourdan as the heartless aristocrat and Christopher Kent as the law-clerk-turned philanderer. In the “Prelude” we can hear the full torment of Emma Bovary’s unsatisfied and unsatisfiable craving for the unreachable—all her “terrifying capacity for pursuing the impossible.” “Romance” reflects the idyllic start of her relationship with Charles Bovary and something of his homely, trusting nature; but Emma, though conscience-stricken at the thought of betraying that trust, nonetheless responds with increasing ardour to Dupuis the clerk’s insistent love-making (“Torment,” with its warm sensuous string lyricism contrasting with the cool innocent-sounding flutes and clarinets of “Romance”). “Gavotte” is one of the dances played at the ball given by Emma’s aristocratic admirer Rodolphe, the climax of which is the celebrated “Madame Bovary Waltz.” Starting in formal, elegant vein, the waltz gradually gathers momentum through changing melodic patterns and culminates in a hysteria of ecstasy. This is, of course, the original version of the waltz, not the revision Rózsa later recorded for his Great Movie Themes album; this earlier, rather longer version has perhaps a keener edge, a surer touch of fire and incandescence.

Ivanhoe and Plymouth Adventure revealed the lengths Rózsa was prepared to go to ensure a period authenticity in a historical drama; they also revealed his flair for encompassing an intensity of emotion within the confines of a period stylistic convention. Ivanhoe (after the novel by Sir Walter Scott) was set in 12th century Saxon England, and because contemporary Saxon culture (or lack of it) was much influenced by that of the invading Normans, Rózsa turned to French sources of the period, which meant the music of the troubadours and trouveres. Some of the themes are so borrowed or adapted, others are the composer’s own—though it is hard to tell where one leaves off and the other takes over. Ivanhoe’s own theme, sturdy and square-built, dominates the “Prelude,” and under the narration which follows, Rózsa quotes from a Ballade actually composed by Richard Couer-de-Lion who is, of course, one of the characters represented in the film. “The Normans” gallop through Sherwood Forest to a splendidly rhythmic Latin hymn by a 12th century troubadour, whilst “Lady Rowena” (the Ivanhoe-Rowena love theme) is a free adaptation of an old popular song from the North of France which, as Rózsa well says, “breathes the innocently amorous atmosphere of the Middle Ages.” In Rózsa’s tender and loving hands it lives all over again. The darkly passionate melody for Rebecca of York (“Rebecca’s Love”) is derived from medieval Jewish sources. The themes of Ivanhoe and the Normans wage war one upon another in “The Battle of Torquilstone Castle” and, for good measure, at least three new themes join the fray, including one for the battering-ram; in the “Finale” King Richard arrives to claim the Crown of England. Rebecca returns to her own people, and Ivanhoe is the hero of the hour.

Plymouth Adventure was the story of the Mayflower’s journey from Plymouth Harbor to Plymouth Rock in 1620, and Rózsa modeled several of his themes on the music of the 17th century English lutenists. The tragic theme for Dorothy Bradford (Gene Tierney) does outwardly so conform, but the emotional substance of the music is basic Rózsa—as we can plainly hear in the scene where, torn between love for her husband and for the Mayflower’s captain, Christopher Jones, she decides to throw herself overboard (“Dorothy’s Decision”). Jones himself (Spencer Tracy) has a brooding, introspective theme, linked of course to Dorothy’s (“The Passion of Christopher Jones”). “John Alden and Priscilla” have a sunny love-theme which begins in the manner of a sarabande but later acquires the salt-water tang of a sea-shanty in a scintillating scherzando episode. The thematic kernel of the score is, however, the 136th Psalm, taken from the one book with music the pilgrims had on board with them when they sailed, namely Henry Ainsworth’s Psalter. Rózsa gives the tune a muscular, forthright choral setting in the “Prelude” and in the finale (“Plymouth Rock”); and in “The Mayflower” it crowns an orchestral climax of towering magnificence as the vessel’s sails billow in the wind and she sets course with pioneer fearlessness toward the unknown region.

We have only to listen to this record or see the films to appreciate the strength, originality and beauty of these classic scores. What we should also remember, however, is that they established a new norm of integrity in the musical treatment of historical dramas, one whose repercussions may still be felt to this day. — Christopher Palmer